If something is poisonous, most people don’t eat it.If something smells awful, they avoid it.

But in Japan, that’s not always the case.

Instead of giving up, Japanese people ask themselves:

“Is there a way to make this safe and delicious?”

Through trial, error, and centuries of culinary evolution, they’ve turned the inedible into edible—and sometimes even into delicacies.

Here are 4 extreme examples that prove Japan’s obsession with food is on another level.

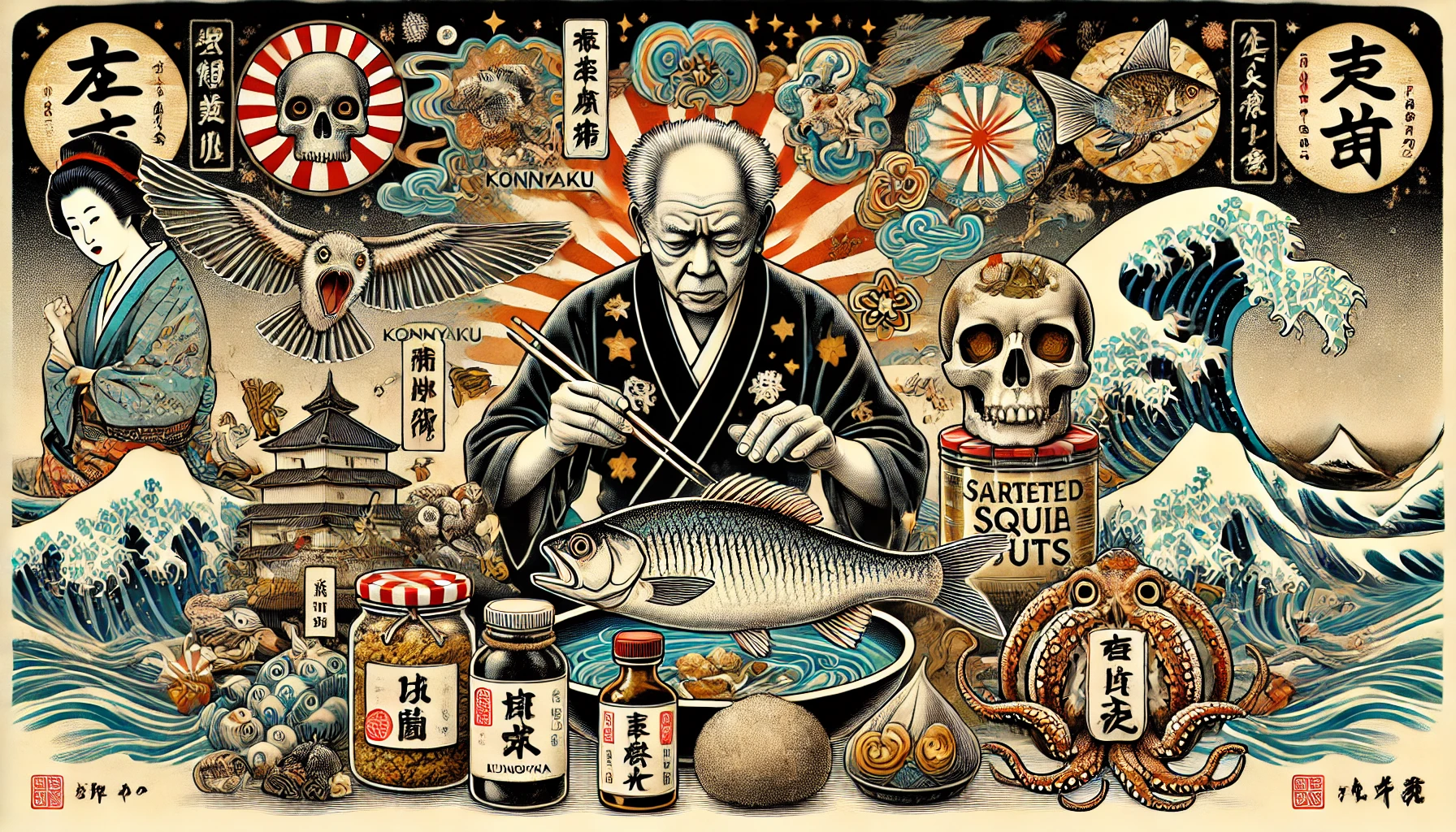

1. Konnyaku – A Healthy Food Made from Poison!?

You may know konnyaku as a jelly-like, low-calorie food often used in Japanese hot pots.

But did you know the raw plant it comes from—konjac root—is actually poisonous?

It contains calcium oxalate crystals, which can cause severe irritation if eaten raw.

Despite that, Japanese people found a way to make it edible:

• First, they boil the root to neutralize toxins

• Then, they mash it into a paste

• Finally, they mix it with limewater to solidify it into konnyaku

It’s a long, complicated process—so why go through all that?

Because the result is a filling, healthy, and versatile food that’s now a staple in Japanese cuisine.

Whoever discovered this process must have been seriously determined… or just very hungry.

2. Fugu – A Deadly Fish That’s Also a Luxury?

Fugu, or pufferfish, is infamous for one thing: it can kill you.

Its liver and ovaries contain tetrodotoxin, a deadly poison with no known antidote.

Yet despite the danger, fugu is considered a high-end delicacy in Japan.

Only chefs with a special government license are allowed to prepare it.

One mistake, and it could be fatal.

What’s even more shocking is that in Ishikawa Prefecture, people eat fugu ovaries fermented in rice bran—a process that takes over two years to remove the toxins.

Why go through such a lengthy, risky process just to eat a fish?

That’s Japan’s culinary obsession at work.

3. Kusaya – The Smelliest Fish You’ll Ever Love?

Kusaya is a type of fermented dried fish from the Izu Islands, and it has one legendary reputation:

It stinks. A lot.

People say it smells worse than durian or even dirty socks left out in the sun.

That smell comes from the kusaya brine—a special liquid made from fermented fish guts that has been reused for hundreds of years.

But here’s the twist: despite the smell, kusaya tastes incredibly rich and umami-packed.

Many Japanese people love it, especially as a snack with sake or shochu.

It’s the ultimate “don’t judge a food by its smell” experience.

4. Salted Squid Guts and Sea Urchin – Turning Leftovers into Luxury

Japanese cuisine is full of examples where parts that would normally be thrown away become the highlight of a dish.

Case in point: squid guts and salted sea urchin (uni).

• Shiokara is made from raw squid and its innards, salted and fermented.

It’s slimy, salty, and has a strong flavor that pairs perfectly with alcohol.

• Salted uni is sea urchin preserved in salt, a method that keeps it edible for longer while concentrating its flavor.

Both are proof of Japan’s zero-waste, full-use philosophy—and its never-ending drive to extract flavor from every last part of an ingredient.

But Why? The Cultural Roots of This Culinary Obsession

So, why do Japanese people go to such lengths to eat something—sometimes even risking their lives or enduring intense smells?

It’s more than just being adventurous.

This obsession is deeply rooted in Japanese culture and history.

Japan has long held a deep respect for nature. Surrounded by mountains, forests, and seas, people have always been mindful of using nature’s gifts wisely. That’s why wasting food is considered shameful—this is where the famous Japanese idea of “mottainai” (too good to waste) comes from.

Instead of throwing things away, Japanese people came up with creative ways to preserve, ferment, detoxify, and enhance flavor.

Over time, these efforts evolved into cultural traditions.

Health is also a major factor. Japan is one of the world’s longest-living countries, and many point to fermented foods—like miso, natto, and yes, kusaya—as part of the reason. These foods support gut health, immunity, and longevity.

Lastly, Japanese culture is extremely open to adopting and adapting new ingredients and techniques, often transforming them into something entirely unique.

That creative spirit helps explain why “inedible” things become gourmet masterpieces here.

Final Thoughts

Japanese food isn’t just about flavor—it’s about philosophy.

Every bite tells a story of ingenuity, respect, and resilience.

So the next time you encounter something strange, smelly, or even a little dangerous on a Japanese menu…

Just remember: there’s probably a centuries-old reason why it’s there.

And who knows? You might just love it.

Recommended Articles

Comments